Notre-Dame de la Garde

| Basilica of Our Lady of the Guard | |

|---|---|

Basilique Notre-Dame de la Garde | |

Notre-Dame de la Garde, seen from the city centre | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| District | Archdiocese of Marseille |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica |

| Year consecrated | 1864 |

| Location | |

| Location | Marseille, France |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°17′03″N 5°22′16″E / 43.2841°N 5.3710°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Byzantine Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1853 |

| Completed | 1897 |

| Materials | Stone |

Notre-Dame de la Garde (French pronunciation: [nɔtʁ(ə) dam d(ə) la ɡaʁd]; lit.: Our Lady of the Guard), known to local citizens as la Bonne Mère (French for 'the Good Mother'), is a Catholic basilica in Marseille and the city's best-known symbol. The site of a popular Assumption Day pilgrimage, it is the most visited site in Marseille.[1] It was built on the foundations of an ancient fort at the highest natural point in Marseille, a 149 m (489 ft) limestone outcropping on the south side of the Old Port of Marseille.

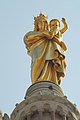

Construction of the basilica began in 1853 and lasted for over 40 years. It was originally an enlargement of a medieval chapel but was transformed into a new structure at the request of Father Bernard, the chaplain. The plans were made and developed by the architect Henri-Jacques Espérandieu. It was consecrated while still unfinished on 5 June 1864. The basilica consists of a lower church or crypt in the Romanesque style, carved from the rock, and an upper church of Neo-Byzantine style decorated with mosaics. A square 41 m (135 ft) bell tower topped by a 12.5 m (41 ft) belfry supports a monumental 11.2 m (37 ft) statue of the Madonna and Child, made of copper gilded with gold leaf.

An extensive restoration from 2001 to 2008 included work on mosaics damaged by candle smoke, green limestone from Gonfolina which had been corroded by pollution, and stonework that had been hit by bullets during the Liberation of France. The restoration of the mosaics was entrusted to Marseille artist Michel Patrizio, whose workmen were trained in Friuli, north of Venice, Italy. The tiles were supplied by the workshop in Venice that had made the originals.

History

[edit]

The rocky outcrop upon which the basilica would be built is an Urgonian limestone, peak dating from the Barremian and rising to a height of 162 metres (531 ft) above sea level.[2] Its height and proximity to the coast caused the hill to become an important stronghold and lookout point and a landmark for sailing. In 1302, Charles II of Anjou ordered one of his ministers to set beacons along the Mediterranean coast of Provence. One of the beacon sites was the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde.[3]

First chapel

[edit]

In 1214, maître (master) Pierre, a priest of Marseille, was inspired to build a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary on the hill known as La Garde, which belonged to the abbey of Saint-Victor. The abbot granted him permission to plant vines, cultivate a garden and build a chapel.[4] The chapel, completed four years later, appears in a June 18, 1218 papal bull by Pope Honorius III listing the possessions of the abbey. After maître Pierre died in 1256, Notre-Dame de la Garde became a priory. The prior of the sanctuary was also one of four claustral priors of Saint-Victor.[5]

From the time that the chapel was founded, surviving wills showed bequests in its favour.[5] Also, sailors who survived shipwrecks gave thanks and deposited ex-votos at Notre-Dame of the Sea in the church of Notre-Dame-du-Mont. Towards the end of the 16th century, they began going to Notre-Dame de la Garde instead.[6]

The first chapel was replaced at the beginning of the 15th century by a larger building with a richly equipped chapel dedicated to Saint Gabriel.[7]

Fort and place of worship from 16th to 18th centuries

[edit]Charles II d'Anjou mentioned a guardpost in the 15th century,[8] but the present basilica was built on the foundations of a 16th-century fort erected by Francis I of France to resist the 1536 siege of Marseille by the Emperor Charles V during the Italian War of 1536–38.

Visit of Francis I

[edit]

On January 3, 1516, Louise of Savoy, the mother of Francis I of France, and his wife, Queen Claude of France, daughter of Louis XII, went to the south of France to meet the young king, right after from his victory at Marignan. On January 7, 1516, they visited the sanctuary. On January 22, 1516, Francis accompanied them to the chapel as well.[9]

The king noted during his visit that Marseille was poorly defended. The need to reinforce its defenses became even more obvious in 1524 after the Constable of Bourbon and emperor Charles V lay siege to the city and almost took it. François I built two forts: one on the island of If, which became the famous Chateau d'If, the other at the top of La Garde, which included the chapel. This is the only known example of a military fort sharing space with a sanctuary open to the public.[10]

The Chateau d'If was finished in 1531, while Notre-Dame de la Garde was not completed until 1536, when it was used to help repel the troops of Charles Quint. It was built using stone from Cap Couronne, as well as materials from buildings outside the ramparts of the demolished city to keep them from providing shelter to enemy troops.[11] Among these was the monastery of the Mineurs brothers where Louis of Toulouse was buried near the Cours Belsunce and Cours Saint-Louis.[12]

The fort was a triangle with two sides of approximately 75 metres and a third of 35 metres. This rather modest fort remains visible on a spur[who?] west of the basilica, which was restored in 1993 to its original state when a 1930 watch tower was removed.

Above the door can be seen a very damaged escutcheon of François I, the arms of France, three fleurs-de-lys with a salamander below. Nearby, to the right, is a rounded stone weathered by time which once represented the lamb of John the Apostle with its banner.[13]

Wars of religion

[edit]

In 1585 Hubert de Garde de Vins, chief of the Catholic League of Provence, sought to seize Marseille and combine forces with Louis de La Motte Dariès, the second consul of Marseille, and Claude Boniface, captain of the Blanquerie neighborhood. On the night of April 9, 1585, Dariès occupied La Garde, from which his guns could fire on the city. But the attack on Marseille failed, leading to the execution of Dariès and his accomplice, Boniface.[14]

In 1591 Charles Emmanuel, Duke of Savoy, tried to seize the Abbey of Saint Victor, a stronghouse near the port. He charged Pierre Bon, baron de Méolhon, governor of Notre-Dame de la Garde, with seizing the abbey. On November 16, 1591, Méolhon did so but it was quickly retaken by Charles de Casaulx, first consul of Marseille.[14][15] in 1594. He sent two priests, Trabuc and Cabot, to celebrate mass in the chapel. Trabuc wore armour under his cassock and after the ceremony killed the captain of the fort. Charles de Casaulx took possession of it and named his son Fabio its governor.[16] After the assassination of Charles de Casaulx on February 17, 1596, by Pierre de Libertat, Fabio was driven out of the fort by his own soldiers.[17]

Last royal visit

[edit]While in Marseille on November 9, 1622, Louis XIII rode in spite of the rain to Notre-Dame de la Garde. He was received by the governor of the fort, Antoine de Boyer, lord of Bandol.[18] When the latter died on June 29, 1642, Georges de Scudéry, mainly known as a novelist, was named governor, but he did not take up his post until December 1644.

He was accompanied there by his sister, Madeleine de Scudéry, a woman of letters who gave in her letters many descriptions of the area as well as of various festivals and ceremonies. "Last Friday... you could see the citadel covered from head to foot with ten or more flags, the bells of our tower swinging, and an admirable procession returning to the castle. The statue of Notre-Dame de la Garde holding in her left arm the naked child and in her right hand, a bouquet of flowers, was carried by eight shoeless penitents veiled like ghosts."[19]

Georges de Scudéry scorned the fort and preferred to live at Place de Lenche, the aristocratic quarter of the time. The stewardship of the fort was entrusted to a mere sergeant, named Nicolas.[20]

In the 1650 Caze affair, the governor of Provence, the Count of Alais, opposed the Parliament of Provence in the Fronde and wanted to put down the revolt in Marseilles. Since La Garde was a desirable strategic position, he bribed Nicolas and on August 1, 1650, installed there one of his men, David Caze. He hoped to support an attack by galleys from Toulon, a city faithful to him.[20] The consuls of Marseille reacted to this threat by forcing David Caze to leave the fort.[21]

18th century

[edit]In 1701, the Dukes of Burgundy and of Berry, grandsons of Louis XIV, visited the sanctuary. Sébastien Vauban, who succeeded Louis Nicolas de Clerville, the builder of Fort Saint Nicolas, studied ways to improve Marseilles' defences. On April 11, 1701, he presented an imposing proposal for a vast enclosure connecting Fort Saint Nicolas to Notre-Dame de la Garde and continuing to the plaine Saint-Michel, currently Place Jean-Jaurès, and the quay d'Arenc.[22] This project was not followed through.

During the Great Plague of Marseille, which killed 100,000 people in Marseille in 1720, the bishop Henri de Belsunce went three times on foot to the chapel at the Notre-Dame de la Garde on September 28 December 8, 1720; and August 13, 1721, to bless the inhabitants of the city.[23]

Revolutionary period

[edit]Closing of the chapel

[edit]On April 30, 1790, the fort was invaded by anti-clerical revolutionaries who crossed the drawbridge on the pretext of attending mass in the chapel, a ruse previously adopted by the ligueurs in 1594.[24] On June 7, 1792, Trinity Sunday, the day's traditionally large procession was disturbed by demonstrations. During the statue's return to the sanctuary, the Virgin was wrapped in a scarf in the revolutionary tricolour and a Phrygian cap, icon of the French Revolution, was placed on the head of the baby Jesus.

On November 23, 1793, the church buildings were closed down and worship ceased. On March 13, 1794, the statue of the Virgin, made in 1661 from silver, was melted down at the mint of Marseille, located at 22 Rue du Tapis-Vert at the former convent of Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy.[25]

A prison for princes

[edit]In April 1793, the King's cousin Louis Phillipe, Duke of Orléans was imprisoned in Notre-Dame de la Garde for several weeks, along with two of his sons, the Duke of Montpensier and the Count of Beaujolais, his sister Louise, Duchess of Bourbon, and the Prince of Conti. Despite the lack of amenities in the old apartments of the governor, the prisoners enjoyed the panorama. Each day the Duchess of Bourbon attended mass then went to the fort's terrace and often remained as much as two hours in contemplation. The princess Louise, who painted well, left behind a pencil drawing of Marseille as seen from the Virgin of Notre-Dame de la Garde. The prisoners were then transferred to Fort Saint-Jean.[26]

A providential man: Escaramagne

[edit]

The last of the objects from the sanctuary were auctioned off on April 10, 1795. The chapel was nationalized and rented to Joseph Escaramagne. A former ship's captain who lived in what is now the current place du Colonel-Edon, Escaramagne had a deep devotion to the Virgin. After worship resumed in some parishes, he wrote in September 1800 to the Minister of War, Lazare Carnot, asking to reopen the sanctuary. But prefect Charles-François Delacroix voiced opposition when the minister consulted him.[27] The chapel finally re-opened for worship on April 4, 1807.[28]

Escaramagne bought at auction an 18th-century statue of the Virgin and child from a monastery of the Picpus Fathers that had been demolished during the Revolution. He offered the statue to the La Garde church. The scepter that the virgin had held was replaced by a bouquet of flowers, hence the statue became known as the "Virgin of the bouquet". To make way for a new silver statue created in 1837, this statue was given to the Montrieux charterhouse, then returned in 1979 to the sanctuary.[29] The statue of the Virgin of the bouquet is currently displayed on the altar in the crypt.

Renaissance of the sanctuary

[edit]On the day the chapel of Notre-Dame de la Garde was reopened for worship, a procession started from Marseille Cathedral, bringing to the sanctuary the statue that Escaramagne had bought.[30] The traditional procession of the Fête-Dieu (Corpus Christi Day) resumed in 1814. Julie Pellizzone mentions this event in her diary: "On Sunday June 12, 1814, Fête-Dieu, the gunners of the city guard went in the morning with barefoot penitents to get Our Lady of the Guard and to bring her into town, according to the ancient custom. She was greeted by several cannon blasts. Mass was said, then she was brought here, carried by penitents with their hoods covering their faces, a procession such as had not taken place since the Revolution.[31]

Chapel expansions

[edit]During this period the fort itself went almost unused while the number of people visiting the chapel increased significantly. This increase was so great that the 150 square meter chapel was extended in 1833 with the addition of a second nave, which increased its area to approximately 250 square meters.[32] The bishop of Marseilles, Fortuné de Mazenod, consecrated this chapel in 1834.

Distinguished visitors

[edit]After escaping a shipwreck while returning from Naples, the Duchess of Berry climbed to the chapel on June 14, 1816, and left a silver statuette as an ex voto – although the statue was melted down a few years later.[33]

Marie Therese of France, daughter of Louis XVI and Duchess of d'Angoulême, climbed to Notre-Dame de la Garde on May 15, 1823, which was a day of strong mistral winds. Despite the wind, the duchess remained on the terrace, struck by the beauty of the view.[34]

In 1838 the Virgin of the Guard had another distinguished visitor: François-René de Chateaubriand.[35]

In 1947, Pope John Paul II, then still Father Karol Wojtyla, visited the basilica. [36]

Pope Francis visited the Notre-Dame de la Garde basilica on September 22, 2023.[37]

Black Madonna and Child

[edit]

Thanks to various offerings, notably a gift of 3000 francs that the Duchess of Orleans made while travelling through Marseille in May 1823, a new statue of the Virgin was commissioned to replace the one melted down during the French Revolution. In 1829, Marseilles goldsmith Jean-Baptiste Chanuel, an artisan with a workshop in the Rue des Dominicaines, began work on this statue based on a model by the sculptor Jean-Pierre Cortot. This very delicate work of hammered gold was finished five years later, in 1834. On July 2, 1837, Fortuné de Mazenod blessed the statue on the Cours Belsunce, which was then brought to the top of the hill. It replaced the Virgin of the Bouquet, which was given to the Montrieux Charterhouse.[38] The Virgin of the Bouquet was later returned to the crypt in 1979. The two statues, the Virgin of the Bouquet and the silver Virgin, thus pre-date the basilica where they are displayed.

New church bell

[edit]The rebuilding of the bell tower in 1843 was accompanied by the purchase of not just a new bell but a bourdon commissioned from the Lyons foundery of Gédéon Morel thanks to a special collection among the faithful. It was cast on February 11, 1845[39] and arrived in Marseille on September 19, 1845. It was placed in Jean-Jaurès square and blessed on Sunday October 5, 1845, by Eugène de Mazenod and baptized "Marie Joséphine".[40] The bell's godfather was André-Élisée Reynard, then mayor of Marseille, and the godmother of the wife of shipping magnate Wulfran Puget (born Canaple). Their names are engraved on the bell.[41] On October 7, the bell which weighed 8,234 kilograms (18,153 lb), was placed on a harnessed carriage of sixteen horses. It descended by Thiers Street, Leon Gambetta Alley, the Rue du Tapis-Vert, the Cours Belsunce, Canebière, the Rue Paradis, and the Cours Pierre-Puget. Ten horses were added there to the convoy, bringing their number to twenty-six. On October 8, 1845, the ascent of the bell up the hill began with the help of capstans and continued until Friday October 10, when the bell arrived at the summit. The bell was set up on Wednesday October 15.[42] It rang out its first notes on December 8, the day of Immaculate Conception.[43]

On this occasion the poet Joseph Autran composed a poem:

- "Sing, vast bell! sing, blessed bell

- Spread, spread afloat your powerful harmony;

- Pour over the sea, the fields, the mounts;

- And especially from this hour when your hymn begins

- Ring out into the skies a song of immense joy

- For the city that we love!"[44]

Like the statues of the Virgin displayed in the interior of the basilica, the bell came before the construction of the current building.

Construction of the current basilica

[edit]Negotiations with the army

[edit]On June 22, 1850, Father Jean-Antoine Bernard, who took responsibility for the chapel, asked the Ministry of War to authorise an expansion of the existing building. This request was denied on October 22, 1850, the day he resigned, by Minister of War Alphonse Henri d'Hautpoul, for being too vague. He agreed to the expansion in theory but invited a more precise proposal.[45] On April 8, 1851, a more precise request was submitted, calling for the construction of a new and larger church, essentially doubling the area of the existing building. This design would mean that there would no longer be room for military buildings inside the fort.[46] Thanks to the support of General Adolphe Niel, the fortifications committee advocated the proposal on January 7, 1852. Authorization to build a new chapel was given by the Minister of War on February 5, 1852.[47]

Project set-up

[edit]On November 1, 1852, Monseigneur Eugene de Mazenod requested offerings from the members of the parish. Studies were requested from various architects. The administration council of the chapel met with Mazenod almost two months later, on December 30. The proposal presented by Leon Vaudoyer, who worked at the Marseille Cathedral, was the only one of Romano-Byzantine style; the others were Neo-Gothic. Each project received five votes, but the vicar's tie-breaking vote went to Vaudoyer, whose project was commissioned. The plans were in fact drawn up by Henri-Jacques Espérandieu, his former pupil who was only twenty-three years old.[48]

On June 23, 1853, Espérandieu was named as architect and developed the project. While he was Protestant, it does not seem that his religion was a major cause of the difficulties he encountered with the committee in charge of the work. The committee decided, without consulting him, not to open up labour for competitive bidding, but to award it directly to Pierre Bérenger (on August 9, 1853), contractor and architect of the Saint-Michel church. He himself had proposed one of the Neo-Gothic plans and was a close relative of Monseigneur Mazenod.[49] The commission also imposed their choice of artists, such as sculptor Joseph-Marius Ramus and the painter Karl Müller of Düsseldorf, without concern for whether their works would fit within the structure. Karl Müller's commission was later rejected, which allowed the architect to direct mosaics as the decor.[50]

Construction

[edit]The first stone was laid by the bishop of Marseille, Monseigneur de Mazenod, on September 11, 1853. Work began but financial problems quickly developed because the foundations had to be laid in very hard rock. In 1855, the government authorized a lottery, but this produced less revenue than anticipated.[51] The financial shortfall grew larger when the sanctuary commission decided to enlarge the crypt to run not only under the choir, but to extend under the entire higher vault. In spite of a loan secured by the personal assets of the bishop, building stopped from 1859 to 1861, the year of Mazenod's death. The new bishop, Patrice Cruice, arrived at the end of August in 1861, and resumed work. The generosity of citizens of all religions and all social positions allowed completion of the work, from the Emperor Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie, who visited Notre Dame de la Garde on September 9, 1860, to the poorest of Marseillais. The sanctuary was dedicated on Saturday June 4, 1864, by the Cardinal of Villecourt, a member of the Roman curia, in the presence of forty-three other bishops. In 1866, mosaic flooring was laid in the upper church and the square bell tower was finished; the bell was installed in October of the same year.

In 1867, a cylindrical pedestal or belfry was built on the square bell tower to receive the monumental statue of the virgin. The statue was financed by the town of Marseille. Sketches for the statue made by three Parisian artists, Eugène-Louis Lequesne, Aimé Millet and Charles Gumery were examined by a jury of Espérandieu the architect, Antoine-Théodore Bernex, mayor of Marseilles, and Philippe-Auguste Jeanron, director of the School of Fine Arts, Antoine Bontoux, sculptor and professor of sculpture and Luce, president of the Civil Court and administrator of the sanctuary. The committee selected the proposal of Lequesne.[52]

For reasons of cost and weight, copper was chosen as the medium for the statue. A very new method for the time was adopted to realize of the statue: galvanoplasty, a type of electroplating, or "the art of moulding without the help of fire"[53] was chosen over hammered copper. A scientific report of November 19, 1866, said that electrotype copper allowed an "irreproachable reproduction" and a solidity that left nothing to be desired. Only Eugène Viollet-le-Duc thought that the galvanoplasty technique would not long resist the atmospheric pollution in Marseilles.[54]

Espérandieu had the statue made in four sections because of the difficulty of getting it up the hill and to the top of the bell tower. He inserted into the center of the sculpture an iron arrow, the core of a spiral staircase to the Virgin's head, to be used for maintenance and sight-seeing. This metal structure, used to support the statue, made it possible to assemble the whole by connecting it to the body of the tower. The execution of the statue, entrusted to the workshops of Charles Christofle, was finished in August 1869.

The first elements were assembled on May 17, 1870, and the statue was dedicated on September 24, 1870, but without fanfare, since defeat by the Prussian army dampened all spirits.[55] The statue was gilded, which required 500 grams (18 oz) gold, and regilding in 1897, 1936, 1963 and 1989.[56]

In March 1871 Gaston Crémieux formed the revolutionary Commune of Marseille. Helped by followers of Giuseppe Garibaldi, the rebels seized the Prefecture of the Rhone delta and took the prefect captive. On March 26, 1871, General Henri Espivent de Villesboisnet retreated to Aubagne, but undertook to retake the city beginning on April 3.[57] The rebels who took refuge in the prefecture took fire from the batteries installed in Fort Saint Nicolas and in Notre-Dame de la Garde. They capitulated on April 4 and said that the Virgin had changed her name and should from then on be called "Notre-Dame of bombardment"[58]

Following the death of Espérandieu on September 11, 1874, Henri Révoil was charged with finishing the interior of the basilica, in particular the mosaics. The construction of the major crypt and installation of the mosaics in the choir was carried out in 1882. Unfortunately a fire on June 5, 1884, destroyed the altar and the mosaic in the choir; moreover the statue of the Virgin was damaged. The statue and the mosaics were restored and the altar was rebuilt according to the drawings of Révoil. On April 26, 1886, cardinal Charles Lavigerie consecrated the new crypt.[59] In 1886, walnut stalls were built in the choir; the last mosaics in the side vaults were finished between 1887 and 1892. In 1897, the two bronze doors of the upper church and the mosaic above them were installed and the statue of the Virgin was regilded for the first time. Final completion of the basilica thus took place more than forty years after the first stone was laid.

Funicular

[edit]

In 1892, the Funiculaire de Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde was built to reduce the effort of scaling the hill; this funicular became known as the ascenseur or elevator. The base was at the lower end of Rue Dragon. The upper station led directly onto a footpath to the terrace beneath the basilica, leaving only a short climb to the level of the crypt at 162 m (531 ft). Construction took two years.

The funicular consisted of two cabins each weighing 13 tons when empty, circulating on parallel cogged tracks. The movement was powered by a "hydraulic balance" system: each cabin, in addition to its two floors capable of holding fifty passengers total, was equipped with a 12 cubic meter tank of water.[60] The cabins were linked by a cable; the tank of the descending cabin was filled with water and that of the ascending cabin emptied. This ballasting started the system moving. The vertical distance between the two stations was 84 m (276 ft).[61]

The water collected at the foot of the apparatus at the end of each trip was brought back to the top with a 25-horsepower pump—true horsepower, because the pump was powered by steam. Travel time was two minutes, but filling the upper tank took more than ten minutes, forcing waits between departures, in spite of often considerable crowds. The last adventure after the ascent was crossing the 100-meter footbridge up the steep slope. Built by Gustave Eiffel, the footbridge was only 5 metres (16 ft) wide and very exposed to the mistral winds.

On August 15, 1892, the number of visitors exceeded 15,000,[62] but the advent of the automobile killed the funicular. On September 11, 1967, at 18:30, the funicular was shut down as unprofitable.[63] It was demolished after having transported 20 million passengers over 75 years.

Liberation of France

[edit]On August 24, 1944, General Joseph de Monsabert ordered General Aimé Sudre to take Notre-Dame de la Garde, which was covered in German Army blockhouses. But his orders stipulated "no air raid, no large-scale use of artillery. This legendary rock will have to be attacked by infantrymen supported by armoured tanks".[64] The primary attack was entrusted to Lieutenant Pichavant, who commanded the 1st company of the 7th regiment of Algerian riflemen[65] On August 25, 1944, at 6 am, troops began moving towards the hill, very slowly, because sniping from German riflemen impeded their advance.

One French soldier, Pierre Chaix-Bryan, was familiar with the neighborhood, and knew that at No. 26 Cherchel street, (now Rue Jules-Moulet) a hallway ran through the building to a staircase unknown to the Germans. A commemorative plaque marks this spot today. The Algerian riflemen used this staircase and arrived under the command of Roger Audibert at the Cherchel plateau. Other soldiers took the staircases up the Notre-Dame slope from the boulevard of the same name. The attackers on the northern face came under fire from the blockhouses then were also attacked from the rear by the guns of Fort Saint Nicolas. The support of the tanks was essential.[66]

In the early afternoon the tanks of the 2nd regiment of cuirassiers of the 1 D.B[who?] also attacked from Boulevard Gazzino, now Boulevard André-Aune, and from the church slope. The tank Jeanne d' Arc was hit full force and stopped at the place du Colonel Edon, its three occupants killed. The tank can still be seen today. A second tank, the Jourdan, hit a mine but was protected by a rocky overhang, and so could continue shooting. This had a decisive effect not known until later: the German non-commissioned specialist in charge of the flame throwers was killed by the Jourdan's fire. Because of this a young, inexperienced German soldier prematurely ignited the flame throwers, which allowed the French to spot the site of the guns.[66]

Around 3:30pm a section of the 1st company of the 7th Algerian riflemen under Roger Audibert, joined by Ripoll[who?], took the hill by storm. They were greeted by Monseigneur Borel, who had taken refuge in the crypt. The French flag was hoisted atop the bell tower, although the position was still shelled from the Angelus[who?] and from Fort Saint Nicolas, until they too were retaken. In the evening the German officer who had commanded the German troops at Notre-Dame de la Garde returned. He was wounded and died two days later. The liberation of Marseille took place on the morning of August 28, 1944.[67]

Architecture

[edit]

The exterior of the building features layered stonework in contrasting colours: white Calissane limestone alternates with green sandstone from Golfolina near Florence. Marble and pictorial mosaics in various colours decorate the upper church. A 35 m (115 ft) double staircase leads to a drawbridge, granting access to the crypt and, via another set of stairs, to the church's main entrance.

Crypt

[edit]

The entrance hall under the bell tower features marble statues of Bishop Eugène de Mazenod and Pope Pius IX, both carved by Joseph-Marius Ramus. Staircases on both sides of the entrance lead to the church above.

The Romanesque crypt is composed of a nave with low barrel vaults, bordered by six side chapels corresponding exactly to those of the upper church. Unlike the upper church, the crypt is dim and somber. The side chapels contain plaques with the names of various donors. The side altars are devoted to saints Philomena, Andrew, Rose, Henry, Louis and Benedict Labre.[68]

The main altar was built of Golfolina stone with columns of Spanish marble. Behind the altar is a statue of the Madonna holding a bouquet, the Vierge au Bouquet. Joseph-Elie Escaramagne obtained this statue for the original chapel in 1804. At first the Madonna held a sceptre, but due to the sceptre's poor condition, it was replaced by flowers.[69] Two staircases flanking the main altar lead to the sacristy buildings and the choir above, but they are off-limits to the public.

Bell tower

[edit]

At a height of 41 metres (135 ft), the square bell tower above the entrance porch has two identical storeys of five blind arches, of which the central arch has a window and a small balcony. This is surmounted by a belfry, with each face composed of a three-light window divided by red granite mullions, behind which are abat-sons. The belfry is covered by a square terrace, which is enclosed by a stone balustrade bearing the arms of the city on each side and an angel with a trumpet at each corner. These four statues were carved by Eugène-Louis Lequesne.

From the square terrace a cylindrical bell tower rises to a height of 12.5 metres (41 ft). It is made of sixteen red granite columns, supporting a 11.2 metres (37 ft) tall statue of the Virgin Mary. A staircase within the bell tower leads to the terrace and to the statue, but is off-limits to the general public.

At the base of the tower, bronze doors by Henri Révoil grant access to the church. The central door panels bear the monogram of the Virgin placed within a circle of pearls resembling the rosary. The tympanum above the main entrance is decorated with a mosaic of the Assumption of the Virgin, patterned after a painting by Louis Stanislas Faivre-Duffer.

Upper church

[edit]

The nave's interior is 32.7 m long and 14 m wide. Each side chapel measures 3.8 m by 5.4 m. The interior is decorated with 1,200 m2 (13,000 sq ft) of mosaics as well as alternating red and white marble columns and pilasters. Espérandieu wanted a subtle red that would harmonise with the mosaics and not clash too much with the whiteness of the Carrara marble. Jules Cantini, the marble worker, discovered such a red marble with yellow and white veins in the commune of La Celle near Brignoles, Var. For parts higher up, plaster—i.e. reconstituted marble—was used.

The mosaics were created between 1886 and 1892 by the Mora company from Nimes. The tesserae came from Venice and were manufactured by craftsmen at the height of their art. Each panel comprises nearly ten thousand tesserae per square metre, which means that the basilica contains approximately 12 million small squares of 1 to 2 cm2 (0.31 sq in). The floors are covered with approximately 380 m2 (4,100 sq ft) of Roman mosaics with geometric patterns.[70]

Nave

[edit]The aisles of the nave are divided into three equal parts, each with a central window that illuminates a side chapel. The external pilasters and arches are composed of alternating green and white stones and voussoirs. Basement windows at ground level allow some daylight into the crypt's underground chapels. Since the nave is higher than the side chapels, a clerestory with two-light windows illuminates the domes of the nave, although these windows are not visible form the terrace.

The nave is topped by three cupolas decorated on the inside with similar mosaics: on a field of flowers, doves form a circle around a central floret. The colours of the flowers differ for each cupola: white for the southeastern one, blue for the middle and red for the northwestern cupola. Medallions on the pendentives depict scenes from the Old Testament:

- Mosaics of the southeastern cupola

-

Overview

- Mosaics of the middle cupola

-

Overview

-

Incense burner

The mosaics of the northwestern cupola depict a grapevine, a thorned lily, an olive branch with silver leaves and a date palm.

Transept

[edit]The transept is oriented east to west and lit by two paired windows, each with a rose window above. Above the crossing of the transept is an octagonal tholobate supporting a dome of nine meters in diameter, composed of thirty-two ribs and crowned by a cross. Each outward face of the octagon contains a window flanked by two red granite columns and topped by a triangular pediment. The semicircular apse is adorned with five blind arches on the outside, each flanked by two red granite columns. The sacristy buildings that were added later hide part of the apse.

The inside of the dome is decorated with a mosaic of four angels on a field of gold. The angels hold up a wreath of roses which they offer to the Virgin Mary, represented by her monogram in the middle of the composition. The pendentives at the base of the dome contain representations of the Four Evangelists: Mark symbolized by a lion, Luke by a bull, John by an eagle and Matthew by a man.

The tympanum above the apse depicts the Annunciation of Mary: the archangel Gabriel on the right announces the birth of Jesus to Mary on the left.

- Art of the transept

-

John the Evangelist

-

Central dome

-

Matthew the Evangelist

Choir

[edit]

The white marble altar was designed by Henri Révoil and constructed by Jules Cantini between 1882 and 1886. The base of the altar is formed by five gilded bronze arches resting on colonettes of lapis lazuli. The silver-gilt tabernacle is framed by two columns and two mosaics of doves drinking from a chalice.

Behind the altar, a red marble column topped by a gilded capital supports a statue of Mary, made of hammered silver by the goldsmith Chanuel of Marseille.

The mosaic of the apse's semi-dome depicts a ship in its central medallion. The ship's sail features the monogram of Mary, while a star in the sky shows an intertwined A and M, which stands for Ave Maria. This medallion is surrounded by rinceaux and thirty two birds, including peacocks, parrots, hoopoes, bluethroats, herons, and goldfinches.

The band beneath the semi-dome is decorated with nine medallions, which represent several titles of Mary from the Litany of Loreto: Foederis Arca, Speculum Iustitiae, Sedes Sapientiae, Turris Davidica, Rosa Mystica, Turris Eburnea, Domus Aurea, Vas Spirituale, Ianua Coeli.

Side chapels

[edit]The aisles on either side of the nave house a total of six side chapels. Henri Révoil designed and Jules Cantini constructed the altars; Cantini also created the statue of Peter and made it a gift to the sanctuary. Each altar tomb features the coat of arms of its respective saint. The ceiling of each chapel is decorated with a mosaic, depicting the name and arms of the financer on one side and a symbol of the saint on the other.

|

|

|

| Entrance ← central nave → choir | ||

|

|

|

-

Joseph's chapel

-

Peter's chapel

-

Ceiling of Lazarus' chapel

-

Mary Magdalene's chapel

Long and meticulous restoration: 2001–2008

[edit]By 2001 the interior facades had severely aged. Also, the cathedral's mosaics had been badly restored after the war. After four years of preparatory studies, a major restoration project was launched in 2001 under the direction of the architect Xavier David. The work lasted until 2008, financed by local government agencies and by donations from private individuals and businesses.

External restoration

[edit]Although the majority of the stones used proved very resistant over time, this did not hold true for the green Golfolina stone, a beautiful hard stone which degrades very quickly when exposed to industrial and domestic pollution, especially coal smoke, and was found to be corroded to a depth of 3 to 5 cm.[71] As the original quarry near Florence had been closed for a long time, a new source was sought. A quarry in a vineyard close to Chianti supplied 150 cubic metres of Golfolina. The defective stone was replaced by stone treated to resist pollution.[72] Moreover, rusting metal reinforcements had split some of the stone. Two sets of reinforcements posed a serious problem: those that girdle the top of the bell tower to reinforce against the swinging of the bell, and those around the upper part of the bell tower that supports the monumental statue. Some of the reinforcements were treated with cathodic protection, and others replaced with stainless steel.

Interior restoration

[edit]Interior work was even more important. Some water-damaged stuccos in higher areas had to be redone. Mosaic panels damaged by bullets or shells had earlier been repaired with a poor and rushed technique: missing tiles had been replaced by plaster covered with paint. Moreover, all the mosaics were blackened by candle smoke. Mosaics which threatened to fall apart needed to be consolidated with resin injections. The most damaged part was in the central cupola of the nave, where all the gold mosaics needed to be replaced.

The restoration of the mosaics was entrusted to Marseille artist Michel Patrizio, whose workmen were trained in traditional mosaic skills at the school of Spilimbergo in Friuli, north of Venice. The mosaic tiles were supplied by the Orsoni Venezia 1888 workshop in Venice which had made the originals.

In the arts

[edit]Writers

[edit]Many writers have described the famous basilica, for example:

- Valery Larbaud:

"She who governs the roads of the sea,

Who shines above the waves and the sun,

The giantess standing behind the blue hours,

high gold inhabitant of a long white country,

Christian Pallas of the Gauls.[73] - Paul Arene: "Here the true good mother, the only one, who rules in a gold coat stiff with pearls and rubies, under the dome of Notre-Dame de la Garde, a cupola of hard lapis lazuli encrusted with diamonds for stars, condescended to be angry with me.[74]

- Chateaubriand: "I hastened to go up to Notre-Dame de la Garde, to admire the sea bordered with the ruins the laughing coasts of all the famous countries of Antiquity.[75]

- Marie Mauron: "It is she whom one sees from the sea, first and last on her summit of light hemmed of blue, dominating its Greek Provence which knows or does not know any more that it is it, but the remainder. Who would miss, believer or not, climbing up to the Good mother?[76]

- Michel Mohrt: "And there high on the mountain, the good Virgin, the good mother, looked out this crowd, presided over the traffic in the false identity cards, at the open-air black market behind the Stock Exchange, with all the attacks, all the denunciations, all the rapes, the Good mother of the Garde who takes care on the sailors who are ashore, – as for those who are at sea, let them sort themselves out! "[77]

- André Suarès: "Notre Dame of the Guard is a mast: it oscillates on its skittle. It will take its flight, the basilica, with the virgin who serves as its crest.[78] Thus the basilica perched on the hill of the guard, and the gilded copper statue which they hoisted on the basilica. There, once more, this style which wants to be Roman and Byzantine, without ever succeeding in being a style: neither the force of the Roman, nor the science of the Byzantine."[79]

Painters of the Basilica

[edit]

Many painters have depicted Marseille's port with Notre-Dame's basilica in the background. Paul Signac, who helped to develop pointillism, produced a painting in 1905 that is now shown in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Albert Marquet produced three works. The first was a drawing executed in ink in 1916, shown at Musee National d'Art Moderne in Paris. The second is an oil on canvas painted in 1916 entitled "The horse at Marseille". This painting, now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bordeaux, shows a horse on the port quay with the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde in the background. The third, shown at the Annonciade museum at Saint-Tropez, is called "The Port of Marseille in fog"; the basilica emerges from a misty landscape where the purification of form indicates distance.This painting shows this painter did not always represent the port of Marseilles from the front, moving his easel to the riverbank side, sometimes close to the town hall, to represent the hill of Notre-Dame de la Garde.

Charles Camoin painted two canvases in 1904 featuring Notre-Dame de la Garde: "The Old Port with Barrels", at the Gelsenkirchen museum, and "The Old Port and Notre-Dame de la Garde" shown at the Fine Art museum of Le Havre. This museum also possesses a painting by Raoul Dufy done in 1908, entitled "The Port of Marseille". In 1920, Marcel Leprin made a pastel drawing "Notre-Dame de la Garde Seen from the Town Hall"; this work is in the Petit Palais museum in Geneva. Louis-Mathieu Verdilhan, about 1920 "The Canal from Fort St. John"; the silhouette of Notre-Dame de la Garde is at the rear of the painting with a boat in the foreground. This painting is at the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris.

M.C. Escher produced a wood engraving of the city, entitled Marseille, in 1936.

Bonne Mère

[edit]The people of Marseille regard the Notre-Dame basilica as the guardian and protectoress of the city, hence its nickname Bonne Mère ("Good Mother"), which is also a nickname of Mary, mother of Jesus.

Ex-votos

[edit]

A Mediterranean-style religiosity is expressed here with numerous votive candles and ex-votos offered to the Virgin to thank her for spiritual or temporal favours and to proclaim and recall the grace received.

One of the oldest documents about this practice is a deed of August 11, 1425, in which a certain Jean Aymar paid five guilders for wax images offered in gratitude to the Virgin.[80] During his travels in the south of France at the beginning of the 19th century, Aubin-Louis Millin de Grandmaison was struck by the number of ex-voto at Notre-Dame de la Garde: "The path that leads to the oratory is stiff and difficult. The chapel is small and narrow, but decorated everywhere with tributes from pious mariners: on the ceiling small vessels are suspended with their rigs and have their name registered on the stern; they represent those that the mother of Christ has saved from cruel shipwreck or from the fury of pirates and corsairs".[81] The ceiling of the upper church still features many scale models of recently restored boats and planes.[82]

The walls of the side vaults of the two sanctuaries, the crypt and upper church, are covered with a first level of marble slabs. The upper walls of these side vaults are occupied by painted ex-votos hung in several rows above; the most recent are on the walls of the terraces of the basilica. Most of these ex-votos date only from the second half of the 19th century; earlier ones disappeared during the Revolution. Most depict shipwrecks and storms, but there are also very different scenes: fire, car and railway accidents, bedridden patients, and political and social events. The events of May 68 were the inspiration for one drawing; an Olympique de Marseille flag recalls that the players of the club[who?] mounted a pilgrimage to the basilica after a victory.

Symbol of Marseille

[edit]Visible from the motorways of Marseille and from the train station, the gare Saint-Charles, Notre Dame de la Garde is the city's most well-known symbol. It is the most-visited site in Marseille,[1] and receives hundreds of visitors every day, a number of pilgrims remarkable for a site that with no association with a saint, vision or miracle, nor for that matter with a famous person. For Cardinal Etchegaray, former bishop of Marseille, the Virgin of the Garde "does not merely form part of the landscape like the Chateau d'If or the Old Port, it is the living heart of Marseille, its central artery more than the Canebière. It is not the exclusive property of Catholics; it belongs to the human family that teems in Marseille."[83] Notre-Dame de la Garde remains the heart of the diocese of Marseille, even more so than the cathedral. It was here that Bishop Jean Delay on August 30, 1944, hoped that deep reforms would bring to the poorest more humane and more just living and working conditions. It was also here that Etchegaray compared, in May 1978, the ravages of unemployment to those of the plague of Marseille of 1720.[84]

A museum opened on the site on June 18, 2013, retracing the building's eight-century history. It was officially inaugurated July 11, 2013, with civil and military authorities participating. As with prior renovations, a fundraising appeal received generous support from the public, in addition to gifts from public agencies.

The logo of the popular French soap opera Plus belle la vie, set in Marseille, depicts Notre-Dame de la Garde. The Marseille-based company Compagnie Maritime d'Expertises used a model of the church for a maritime test launch in 2017 where the symbol was sent to near-space in 20 km altitude.[85]

Tourism

[edit]Notre-Dame de la Garde receives around a million and half visitors each year, many just for the view.[9] Pilgrims come for various reasons, some writing them down in a guestbook. One in particular sums up these reasons: "I came here first for the peace and comfort one finds at the feet of the Blessed Virgin, then for the feast for the eyes that the basilica offers, for the panorama, the pure air and the space, for the feeling of freedom."[86]

Gallery

[edit]-

Cupola and transept

-

Statue of the Virgin

-

Interior of the basilica

-

Detail of the cupola

-

Traces left by shrapnel impact

-

Mosaic on the floor of the choir

-

Lateral chapels

-

Bronze door to the entrance

-

Statue of Mazenod at the entrance to the crypt

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bertrand 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Gouvernet, C.; Guieu, G.; Rousset, C. (1971). Guides géologiques régionaux, Marseille. Paris: Masson. p. 198.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, p. 29.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, pp. 13–15.

- ^ a b Chaillan, M. (1931). Petite monographie d'une grande église, Notre-Dame de la Garde à Marseille [Small monography of a big church, Notre-Dame de la Garde in Marseille] (in French). Marseille: Moulot. p. 23.

- ^ Colombière 1855, p. 3.

- ^ Hildesheimer 1985, p. 17.

- ^ Office de tourisme et des congrès de Marseille (2013). "Notre Dame de La Garde". Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Levet 1994, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Levet 1994.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 21.

- ^ Louis Méry et F. Guindon, Histoire analytique et chronologique des actes et des délibérations du corps et du conseil de la municipalité de Marseille, éd. Barlatier Feissat, Marseille, 1845–1873, 7 vol., t. 3, note 1, p.335

- ^ Colombière 1855, p. 12.

- ^ a b Kaiser 1991, p. 266.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 39.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, p. 45.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 46.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 49.

- ^ Bouyala d'Arnaud 1961, p. 365.

- ^ a b Adolphe Crémieux, ..Marseille et la royauté pendant la minorité de Louis XIV (1643–1660), Librairie Hachette, Paris 1917, 2 volumes, p.319

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Levet 1994, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Bouyala d'Arnaud 1961, p. 367.

- ^ Adrien Corns, ' ' Historical dictionary of the streets of Marseille' ', ED. Jeanne Laffitte, Marseilles, 1989, p.360, ISBN 2-86276-195-8.

- ^ Jean-Baptist Samat (1993). "La détention des princes d'Orléans à Marseille (1793–1796)" [The detention of the princes of Orleans in Marseilles (1793–1796)] (59). Comité du Vieux Marseille (Committee of Old Marseilles): 174.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Levet 1994, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 91.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 204.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 93.

- ^ " Julie Pellizzone, Memories, Indigo & Side-women editions, Publications of the University of Provence, Paris, 1995, T. 1 (1787–1815), p.398 ISBN 2-907883-93-3.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 102.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, p. 225.

- ^ Bouyala d'Arnaud 1961, p. 368.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 106.

- ^ "Pope Francis entrusts to Mary 'Mediterranean Encounter' with youth and bishops".

- ^ "À Notre-Dame de la Garde, le Pape invite à la compassion et au pardon - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va (in French). September 22, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 104.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, p. 120.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 109.

- ^ Colombière 1855, p. 36.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, p. 121.

- ^ Bouyala d'Arnaud 1961, p. 369.

- ^ Chagny, André (1950). Notre-Dame de Garde (in French). Lyon: Editions Héliogravure M. Lescuyer & Fils. OCLC 14251718.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 113.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 114.

- ^ Levet 1994, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 120.

- ^ Jasmin, Denise (2003). Henri Espérandieu, la truelle et la lyre [Henri Espérandieu, the trowel and the lyre] (in French). Arles Marseille: Actes-Sud/Maupetit. p. 154. ISBN 2-7427-4411-8.

- ^ Revue Marseilles, January 1997, N° 179, p.84

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 123.

- ^ Archives of Marseille, ' 'Henry Espérandieu, architect of Notre-Dame of Garde' ', ED. Édisud, Aix-en-Provence, 1997, p.32 ISBN 2-85744-926-7.

- ^ Aillaud 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Aillaud 2002, p. 14.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, pp. 146–148.

- ^ Bertrand, Régis; Tirone, Lucien (1991). Le guide de Marseille. Besançon: La manufacture. p. 242. ISBN 2-7377-0276-3.

- ^ Guiral and Paul Amargier, History of Marseille, Mazarine, 1983, p.276.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 144.

- ^ Levet 1994, p. 154.

- ^ Gallocher, Pierre (1989). Marseille, Zigzags dans le passé. Vol. 2. Marseille: Tacussel. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Levet 1992, p. 35.

- ^ Levet 1992, p. 38.

- ^ Levet 1992, p. 89.

- ^ Jean Contruucci, And Marseilles was released August 23–28, 1944, ED. Other Times, Marseilles, 1994, p.65 ISBN 2-908805-42-1.

- ^ L'Amicale du 7ème Régiment de Tirailleurs Algériens (September 1, 2016). "1953 : Marseille a rendu hommage au 7éme R.T.A qui la libera".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Roger Duchêne and Jean Contrucci, Marseille, ED. Beech, 1998, ISBN 2-213-60197-6 p.671.

- ^ Guiral, Paul (1974). Libération de Marseille [Liberation of Marseille] (in French). Hachette. p. 98.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lenzini, José; Garot, Thierry (2003). Notre-Dame de la Garde. Nice: Giletta. p. 109. ISBN 2-903574-91-X.

- ^ "La Crypte de Notre Dame de la Garde" (in French).

- ^ Levet 2008, p. 888.

- ^ Levet 2008, p. 86.

- ^ Revue Marseille, N° 219, p. 94

- ^ "Valery Larbaud, ' 'Oeuvres' ', collection bibliothèque de la pléiade, ED. Gallimard, Paris, 1957, p.1111

- ^ Paul Arène, Contes et nouvelles de Provence, éd. Presses de la Renaissance, Paris, 1979, p. 325, ISBN 2-85616-153-7

- ^ Chateaubriand, Mémoires d’outre-tombe, livre quatorzième, chapitre 2, coll. bibliothèque de la pléiade, éd. Gallimard, Paris, 1951, p. 482

- ^ Mauron, Marie (1954). En parcourant la Provence. Monaco: Les flots bleus. p. 161.

- ^ Michel Mohrt, Mon royaume pour un cheval, éd. Albin Michel, Paris, 1949, p. 39

- ^ Suarès 1976, p. 83.

- ^ Suarès 1976, p. 12.

- ^ d'Agnel 1923, p. 193.

- ^ Aubin-Louis Millin, Travel in the south of France, imperial press, Paris, 1807–1811, four volumes and an atlas, volume 3, p.261.

- ^ "Models of boats donated for answered prayers hang in basilica in Marseille, Olympic sailing host". AP News. August 3, 2024. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ Website of the diocese of Marseilles Archived May 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Hildesheimer 1985, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Marseille dans la stratosphere, La Provence, https://www.laprovence.com/article/mer/4606356/marseille-dans-la-stratosphere.html

- ^ Chélini, Jean (2009). Notre-Dame de la Garde, le cœur de Marseille. Gémenos: Autres temps. p. 17. ISBN 978-2-84521-360-9.

Je viens d'abord pour la douceur et le réconfort qu'on trouve aux pieds de la Sainte Vierge, puis pour le régal des yeux qu'offre la basilique, pour le panorama, pour l'air pur et l'espace, pour la sensation de liberté.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aillaud, G.; Georgelin, Y; Tachoire, H. (2002). Marseille, 2600 ans de découvertes scientifiques, III – Découvreurs et découvertes [Marseille, 2600 years of scientific discoveries, III – Discoverers and discoveries] (in French). Aix-en-Provence: Publications de l’Université de Provence. ISBN 2-85399-504-6.

- d'Agnel, Gustave Henri Arnaud (1923). Marseille, Notre-Dame de la Garde. Marseille: Tacussel.

- Bertrand, Régis (2008). Le Christ des Marseillais [The Christ of the Marseillais] (in French). Marseille: La Thune. ISBN 978-2-913847-43-9.

- Bouyala d'Arnaud, André (1961). Évocation du vieux Marseille [Recalling old Marseille] (in French). Paris: Les éditions de minuit.

- de la Colombière, Régis (1855). Notice sur la chapelle et le fort de Notre-Dame de la Garde (in French). Marseille: Typographie Veuve Marius Olive.

- Hildesheimer, Françoise (1985). Notre-Dame de la Garde, la Bonne Mère de Marseille (in French). Marseille: Jeanne Laffitte. ISBN 2-86276-088-9.

- Kaiser, Wolfgang (1991). Marseille au temps des troubles 1559-1596 (in French). Paris: École des hautes études en sciences sociales. ISBN 2-7132-0989-7.

- Levet, Robert (1992). Cet ascenseur qui montait à la Bonne Mère [This elevator which ascends to the Good Mother] (in French). Marseille: Tacussel. ISBN 2-903963-60-6.

- Levet, Robert (1994). La Vierge de la Garde au milieu des bastions [The Virgin of the Guard within the fortress] (in French). Marseille: Tacussel. ISBN 2-903963-75-4.

- Levet, Robert (2008). La Vierge de la garde plus lumineuse que jamais [The Virgin of the Guard brighter than ever] (in French). Marseille: Association du domaine de Notre-dame de la Garde.

- Suarès, André (1976). Marsiho (in French). Marseille: Jeanne Laffitte.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnaud Ramière de Fortanier, Illustration du vieux Marseille, ed. Aubanel, Avignon, 1978, ISBN 2-7006-0080-0

- Félix Reynaud, Ex-voto de Notre-Dame de la Garde. La vie quotidienne. édition La Thune, Marseille, 2000, ISBN 2-913847-08-0

- Félix Reynaud, Ex-voto marins de Notre-Dame de la Garde. édition La Thune, Marseille, 1996, ISBN 2-9509917-2-6

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Notre-Dame de la Garde – Marseille Tourism

- Bells of Notre-Dame de la Garde

- 6th arrondissement of Marseille

- Roman Catholic churches in Marseille

- Byzantine Revival architecture in France

- Basilica churches in France

- Tourist attractions in Marseille

- 19th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in France

- Church buildings with domes

- Roman Catholic churches completed in 1864

- Pilgrimage churches